This blog post originally appeared on crypto.is. We've since shut down that website, so I have copied the blog post back to my own for archival purposes.

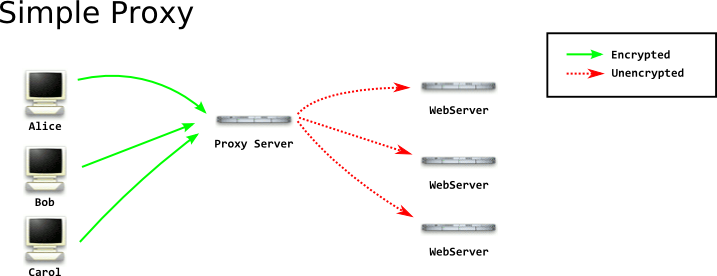

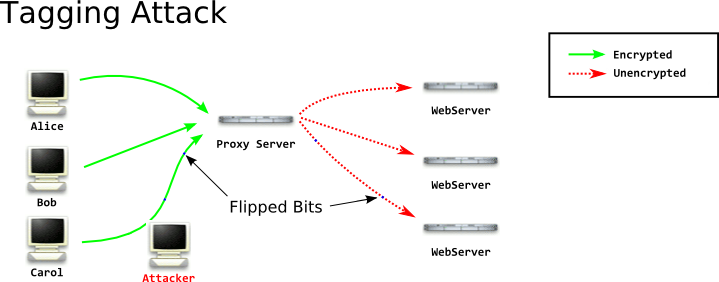

A Tagging Attack is a class of attack that allows an adversary to recognize traffic at a later date by modifying it. It may be best illustrated by an example. Consider a simple example, where clients communicate with a server using AES in CTR mode, with a pre-shared key for simplicity.

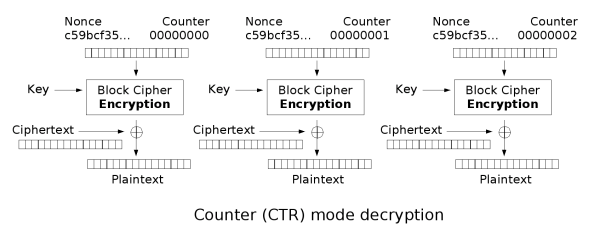

An attacker observes the N clients connected to the server, and sees the outgoing connections to websites, but cannot be certain which client is requesting which resource. The attacker can use a tagging attack to be certain what resource a client is requesting. For the purposes of this illustration we will ignore the passive length-based correlation available to the attacker, and focus on the tagging attack. CTR decryption works by XORing the ciphertext with the keystream to produce the plaintext:

An attacker will modify the ciphertext slightly. Specifically, they will XOR the first byte of the ciphertext with 0x20. Why 0x20? Because this is a special value that will allow every party involved to continue as normal, while allowing the attacker to detect the tag. Let's look at it in detail. Consider the following Plaintext, Keystream, and Ciphertext.

HTTP: G E T / H T T P / 1 . 1 \n H o s t : ...

Plaintext: 47 45 54 20 2f 20 48 54 54 50 2f 31 2e 31 0A 48 6f 73 74 3a ...

Keystream: c3 91 f0 c3 74 90 cf dd 91 24 5c 65 1d 2c bd 79 1b 99 48 c0 ...

XOR: -----------------------------------------------------------

Ciphertext: 84 D4 A4 E3 5B B0 87 89 C5 74 73 54 33 1D B7 31 74 EA 3C FA ...

The attacker sees this ciphertext as it leaves the client, and will modify the first byte of it.

Ciphertext: 84 D4 A4 E3 5B B0 87 89 C5 74 73 54 33 1D B7 31 74 EA 3C FA ...

Attacker: 20

XOR: -----------------------------------------------------------

Ciphertext':A4 D4 A4 E3 5B B0 87 89 C5 74 73 54 33 1D B7 31 74 EA 3C FA ...

Now the server will recieve it and produce the same keystream, decrypt it, and forward it on to the appropriate server.

Ciphertext':A4 D4 A4 E3 5B B0 87 89 C5 74 73 54 33 1D B7 31 74 EA 3C FA ...

Keystream: c3 91 f0 c3 74 90 cf dd 91 24 5c 65 1d 2c bd 79 1b 99 48 c0 ...

XOR: -----------------------------------------------------------

Plaintext: 67 45 54 20 2f 20 48 54 54 50 2f 31 2e 31 0A 48 6f 73 74 3a ...

HTTP: g E T / H T T P / 1 . 1 \n H o s t : ...

But observe what the attacker has done! The attacker has changed the uppercase GET to gET. No client will send a HTTP request in that form, but no server will reject it. The attacker then knows that whatever request comes out in that form was from the client they modified going in. A cool thing about this value is that it will also change POST to pOST, so it works on both requests.

Applicability To Cryptographic Primatives

Tagging attacks are easiest when the underlying cryptographic primative is homomorphic with regards to an operation. That's a fancy way of saying the ciphertext may be modified by an operation, and the modification affects the plaintext in the same way. Homomorphic encryption is a bit of a buzzword, so hearing that RSA is homomorphic may come as a surprise - but it's true. RSA, and a number of other primitives, are partially homomorphic. Only bare RSA is homomorphic, padded RSA is not. For this and many more reasons - never use bare RSA.

And as demonstrated earlier, block cipher modes may also be homomorphic. We demonstrated a tagging attack on Counter Mode (CTR), it is similarly trivial in Output Feedback Mode (OFB). It is also possible in Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) and Cipher Feedback Mode (CFB). Other block cipher modes may be similarly vulnerable.

However, a tagging attack does not require homomorphism. Homomorphism merely makes the attack easier to weaponize! It's also entirely possible to mangle ciphertext to cause an error, and by observing the response to the error, you can perfom the correlation. In the future, we'll show a practical tagging attack on a real, deployed, anonymity system.

Commonalities Between Passive Correlation Attacks

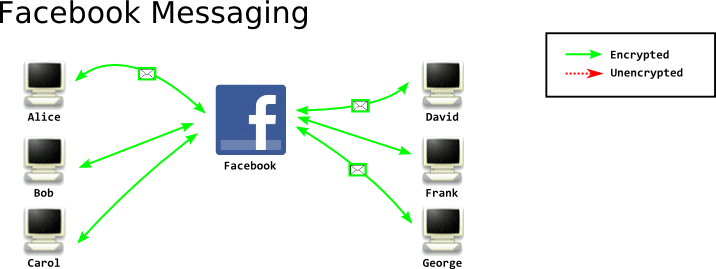

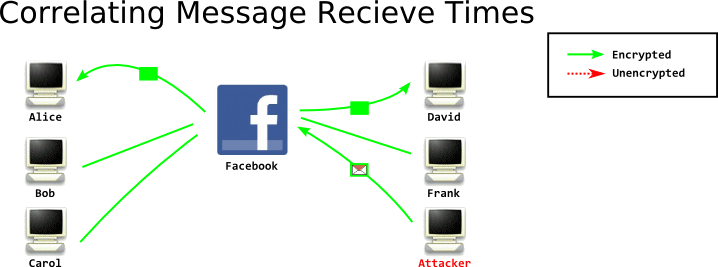

The goal of a tagging attack is to recognize traffic after it traverses an uncontrolled node. However a tagging attack is not the only way to accomplish this goal. In fact, a passive correlation attack may be even easier. Consider a scenario where a number of clients are connected to a Facebook chat server, and they are periodically sending and recieving chat messages:

I want to know which of these connected clients is a particular user on facebook. I have two easy ways to do this. First, I can simply watch which clients recieve messages when I send messages to the user. I can't see inside their traffic, but I can see the size of the traffic, so I know when they recieve a message. In this case, I've narrowed it down to Alice and David. I can keep doing this until I've figured it out conclusively.

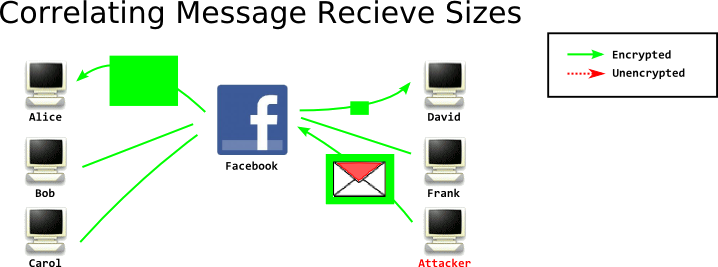

However, if clients are sending and recieving messages constantly, this may be tricky to achieve accurately with a few number of messages. I can get much higher accuracy in a single message... by sending a huge message. Most chats are small, a few sentences. By sending a huge message, up to the maximum limit, I can easily see which client recieves a correspondingly huge message:

This correlation attack does not require an adversary to modify any traffic, so it doesn't fit the standard definition of a 'tagging attack'. This type of correlation, based on packet sizes and timings, are particurally damaging against low latency mix networks like Tor. However, with enough data, they can also work against high latency mix networks like remailers. We're going to talk a lot more about these passive correlation attacks in the future.

Preventing Tagging Attacks

The goal of a tagging attack is to recognize traffic after it traverses an uncontrolled node. Therefore to prevent the attack from succeeding, the uncontrolled node must recognize that the traffic has been tagged, and drop it. The key goal is to provide integrity of the entirity of the message. There are a few different techniques to do so. For example, you can compute a MAC of the ciphertext and transmit that along with the message:

Message: A4 D4 A4 E3 5B B0 87 89 C5 74 73 54 33 1D B7 31 74 EA 3C FA 73 C8 3B A5 9C 7F 1D

|________________________________________________| |___________________________|

Ciphertext MAC of Ciphertext

If the whole of the message is protected with a MAC, and the MAC is computed over the ciphertext, we can recognize any modification. An attacker must modify either the ciphertext or the MAC, and if either is modified the MAC will not verify correctly. If the MAC doesn't verify correctly, the node discards it.

Another technique to provide integrity is to use an authenticated encryption mode. With a correctly implemented authenticated encryption mode, a modification in the ciphertext will result in an exception or error state during decryption, and the node will not have plaintext to use. Another primitive, which is more complicated, is to encrypt the entire message in a single block, using special constructions that allow for large block sizes such as BEAR or LIONESS. If the entire message is a single block, any bit that is flipped will cause the entire block to decrypt to something completely unrecognizable by the intermediate node (hopefully). Using a large block size is generally a very tricky thing, and should not be done without a very deep background in cryptography.

More

Tagging Attacks have been written about before, but generally in academic papers - for more detail, we recommend "One cell is enough to break Tor's anonymity" on the Tor Project blog, and the references it included. However, the security trade-offs made by Tor in relation to tagging attacks should not be accepted as carte-blanche to ignore the attack in new systems. For example, because Tor is a low-latency system, and remailers are a high-latency system, tagging attacks may provide higher confidence levels compared to pure correlation-based attacks.

This blog post is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License and is inspired by, and makes heavy use of, the images produced by the EFF & Tor Project here.

required, hidden, gravatared

required, markdown enabled (help)

* item 2

* item 3

are treated like code:

if 1 * 2 < 3:

print "hello, world!"

are treated like code: